The History Of The Sexual Tipping Point® Model

The Sexual Tipping Point® Model evolved over the last 50 years, initially during two decades of collaboration between Helen S. Kaplan, MD, Ph.D. and Michael A. Perelman, Ph.D.

Perelman was pursuing graduate studies at Columbia University’s clinical psychology program, and concurrently was a Fellow (1974) and Kaplan’s first doctoral student at NY Weill Cornell Medicine’s Human Sexuality Program. Perelman completed the first Ph.D. thesis on sex therapy in Columbia’s history with Kaplan and Raymond C. Rosen, Ph.D. serving as outside readers. Kaplan had Founded at the Payne Whitney Clinic of the New York Hospital in 1973. In 1974 she published The New Sex Therapy, which described that program’s outpatient treatment approach, having modified Masters and Johnson’s (1971) 2-week pioneering residential program. For decades Kaplan’s book became the standard text for most students and medical institutions around the world, and had an impact on where and how people were treated for sexual problems both nationally and internationally. Kaplan brought the principles of multi-determinism and multilevel causality to sex therapy (Perelman, 2014). Kaplan practiced a therapeutic eclecticism that anticipated current sexual medicine approaches that combine/integrate appropriate selection of medical and surgical treatments with sex counseling, first described by Althof, Leiblum, McCarthy, Perelman, Rosen, Segraves, and Wylie, among others, by the turn of the 21st century.

In Kaplan’s final book (1995), she described a "psychosomatic" dual-control model of sexual motivation emphasizing “inhibition/excitation” processes. Kaplan’s concept was derivative of the work of Kupferman (1991) who wrote, “All examples of physiological motivational control seem to involve dual effects—inhibitory and excitatory—which function together to adjust the system” (p. 751). In response to that insight, Kaplan wrote, “Control of sexual motivation is no exception and also operates on such a “dual steering” principle… Once again, we can learn from the similarities between eating and sex” (Kaplan, 1995, p. 17).

Adapted with permission from Kaplan HS, The Sexual Desire Disorders. Dysfunctional Regulation of Sexual Motivation. Brunner-Routledge (Taylor and Frances, London, 1995: p. 15 (Fig. 2)

An artist by training, Kaplan had sketched a cartoon in that 1995 book (Figure 2 on the left) that foreshadowed the current digital graphics developed for use in the Sexual Tipping Point® model, all of which can be seen on this website.

Kaplan’s description and illustration of the dual control elements underlying human sexual motivation and sexual desire dysregulation anticipated Bancroft and his Kinsey Institute colleagues, including Graham, Heiman, Janssen, Sanders, and others. They later provided continuing erudite articulation of dual-control theory, research and related psychometrics becoming the best known of these various models (1999, 2000, 2005, 2009). Kaplan also foreshadowed the work of James Pfaus’ (2006) concepts of satiation of appetite being related to satiation of sexual desire as a theoretical mechanism to explain Hypoactive Sexual Desire Disorder.

Kaplan dedicated that final book to her two-decade collaboration with her colleagues at Cornell. In 1995, having been appointed Co-Director of that program, this author found inspiration from Kaplan’s sketch and refined his own mind/body ideas into the Sexual Tipping Point® model. The initial plan was for the model’s graphics to provide a visual heuristic that assisted Cornell clinicians in training to recognize the intra- and inter-individual variability of all sexual function and dysfunction.

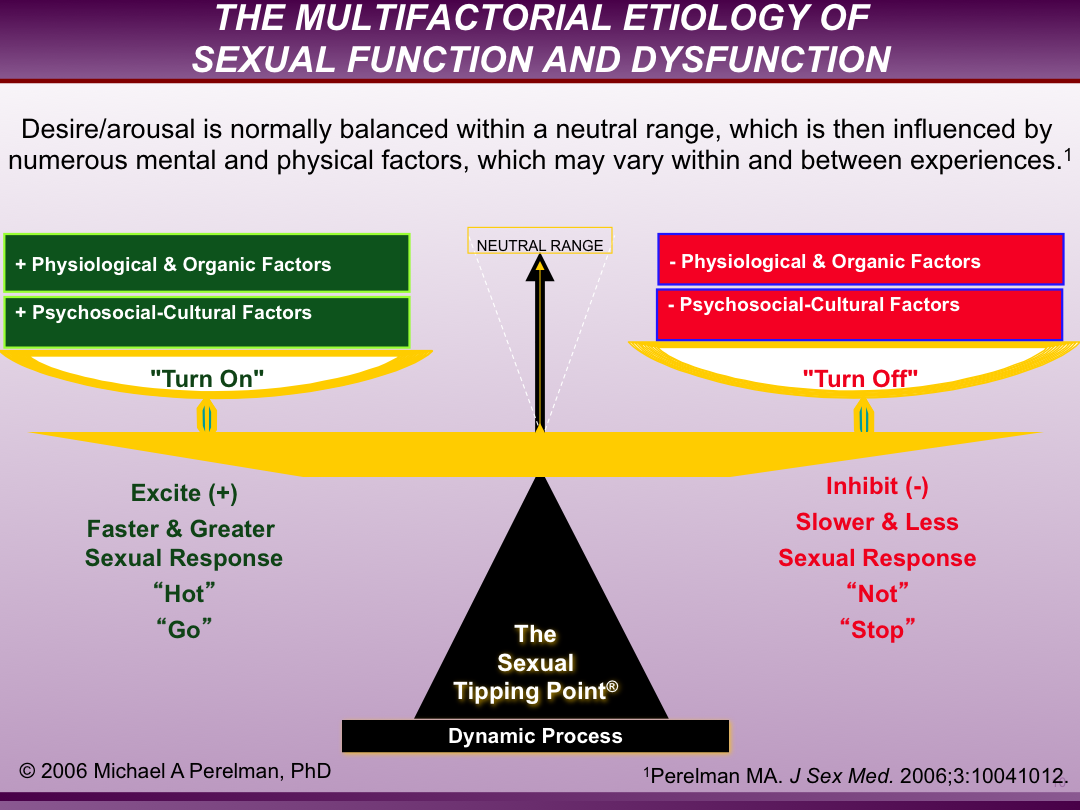

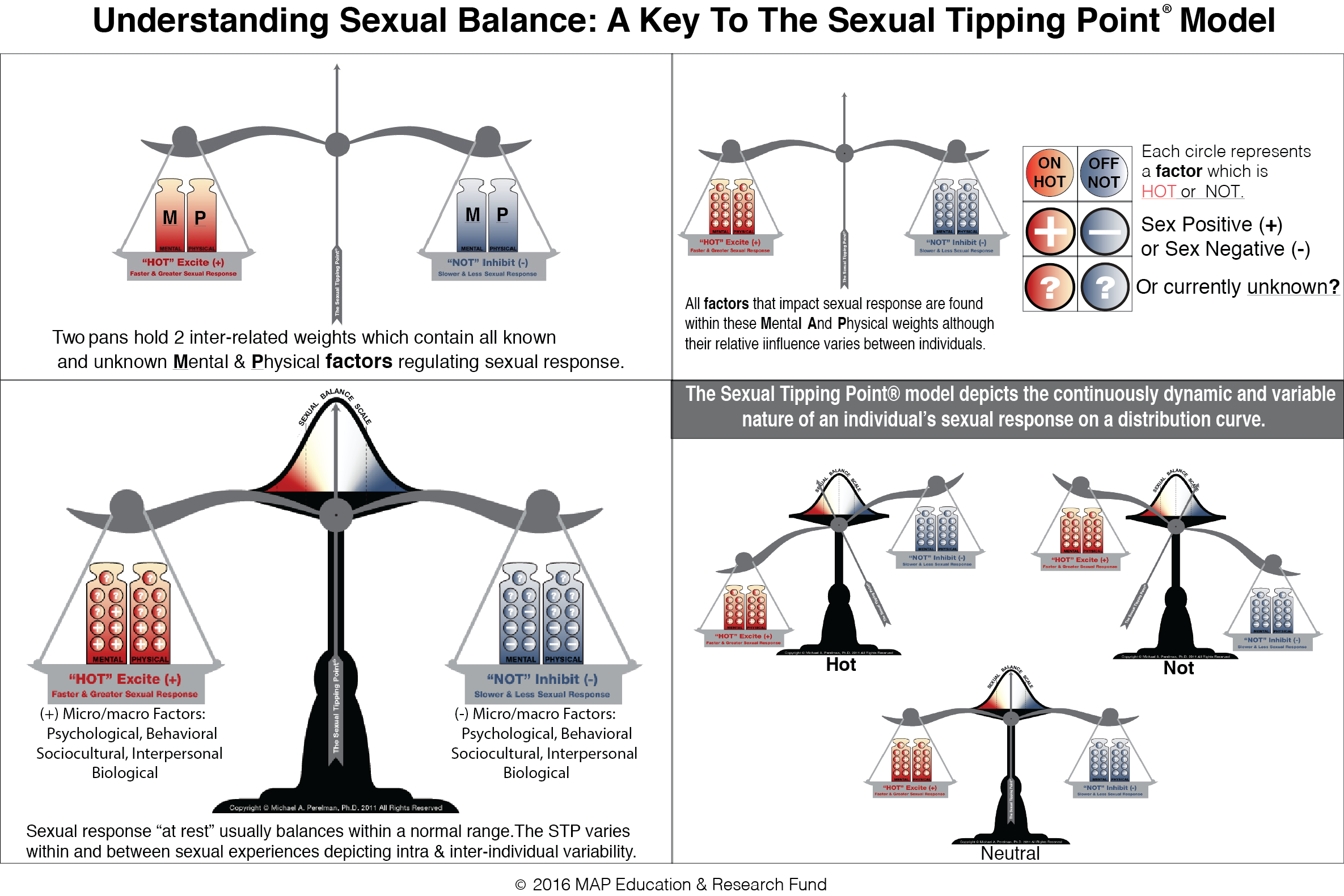

The Sexual Tipping Point® model easily illuminates the mind-body concept that mental factors can “turn you on” as well as “turn you off”; the same is true of the physical factors. The Sexual Tipping Point or STP depicts a person’s moment to moment sexual response (or lack), as regulated by the interaction of their constitutional sexual capacity with biomedical, psychosocial and cultural determining factors. An individuals STP differs from one experience to another, based on the proportional impact of one factor dominating, as others recede in importance. The STP model can illustrate both the intra and inter-individual variability characterizing sexual response and its disorders for both men and women. Initially, the STP was viewed as one of a number of “Dual Control” biopsychosocial models. Instead, by 2018 it was recognized as the first “Variable Control” model (Perelman, 2018). The reason(s) for this theoretical recapitulation are explained later in the below text, but essentially the change reflected advances in our biological, psychosocial and technological knowledge about the human body.

The Sexual Tipping Point® name derived from a concept that was “in the air” at the end of the 20th century. And of course the publication of journalist Malcolm Gladwell’s book made the phrase “The Tipping Point” iconic. However, Gladwell wrote and lectured about social epidemics and other macro forces, such as viral marketing. Distinctly and in contrast the STP was focused on individual uniqueness and the continuous variability of both interpersonal and intrapersonal factors from a biomedical and psychosocial–cultural perspective. The STP’s initial application was to sex therapy; later, it expanded to incorporate all aspects of sexual medicine. To document and distinguish the differences between Gladwell’s exceedingly well-known phrase and the Sexual Tipping Point® model, a trademark registration was sought and awarded by the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office in 2005.

Besides illustrating all etiological permutations, including normal sexual balance, the Sexual Tipping Point® concept is particularly useful for modeling treatment and can easily be used to explain risks and benefits for patients with sexual disorders. The STP model can be used to teach patients where different treatment targets should be focused, depending on diagnosis of their etiological determinants. Typically expressed erroneous binary beliefs can be politely disabused and the patient can be reassured that “No, it is not all in your head,” nor “all a physical problem.” Reciprocally, their partner can be assured it is “not all their fault”! Teaching the STP model to the patient and partner can reduce patient and partner despair and anger, while providing hope through a simple explanation of how the problem’s causes can be diagnosed, parsed, and "fixed” (Perelman & Watter, 2016). In fact, the Sexual Tipping Point® also allows for modeling of a variety of future treatments, including medical or surgical interventions not yet discovered or proven, such as novel pharmacotherapy, genetic engineering or nanotechnology (Perelman, 2011b).

Some ideas embedded within the STP were first incorporated into the author’s presentations on “Sex Coaching for Physicians” (Perelman, 1998) and were also referred to as part of the author’s 1998 Journal of Sex & Marital Therapy commentary on the “Cornell Model.” The author first introduced the “Sexual Tipping Point” term to the professional public in a lecture called “The Role of Sex Therapy, an Overview,” delivered at a CME sexual medicine update course called “Sexual Dysfunction 2001” at Columbia University’s College of Physicians and Surgeons’ Department of Urology. That was also the first time that “Female Sexual Dysfunction” was discussed in that forum, and the STP model was used to illustrate how all the mental and physical factors both implicit and explicit in male sexual dysfunction were also true for disorders and common concerns of women. While obvious to some at the time and to all in retrospect, the profound success of the 1998 launch of sildenafil by Pfizer had overwhelmingly tilted urologists’ attention at the millennium to focus on male disorders with little recognition of the problems and concerns of women.

A number of ensuing presentations and publications described how the STP model could be applied across the full spectrum of specific sexual concerns and disorders. That work led to a presentation at the combined 2008 American Urological Association & Society for Basic Urologic Research summer institute devoted to young investigators interested in the field of sexual medicine. The proceedings of that conference were published in the 2009 Journal of Sexual Medicine, which included the manuscript “The sexual tipping point: a mind/body model for sexual medicine,” expanded awareness of the model. Then Jim Pfaus’ seminal work on sexual desire highlighted the value of the STP model, both catalyzing and advancing its widespread acceptance (Pfaus, 2009).

The graphic representations of the STP have evolved rapidly over the past 20 years. Early images of the STP through 2009 were generated from Microsoft Office graphics and, their resolution was modest as reflected in these illustrations below from 2006.

In 2012, the first retrospective of the various STP images used over the previous decade was presented to the 15th World Meeting of The International Society For Sexual Medicine (ISSM). The poster used to supplement that presentation is shown below.

In 2013, Perelman donated the STP trademark registration to the MAP Education & Research Foundation, Inc., (mapedfund.org) so that organization could distribute STP resources worldwide for free. By then more sophisticated and nuanced figures featuring “building blocks” were available that could be used to assemble unique representations of any given individual’s STP. The Foundation has always maintained a key to those STP images on its homepage and began offering fully narrated video descriptions of the STP Model that may be found on the home page of this website, as well as on YouTube and Vimeo channels.

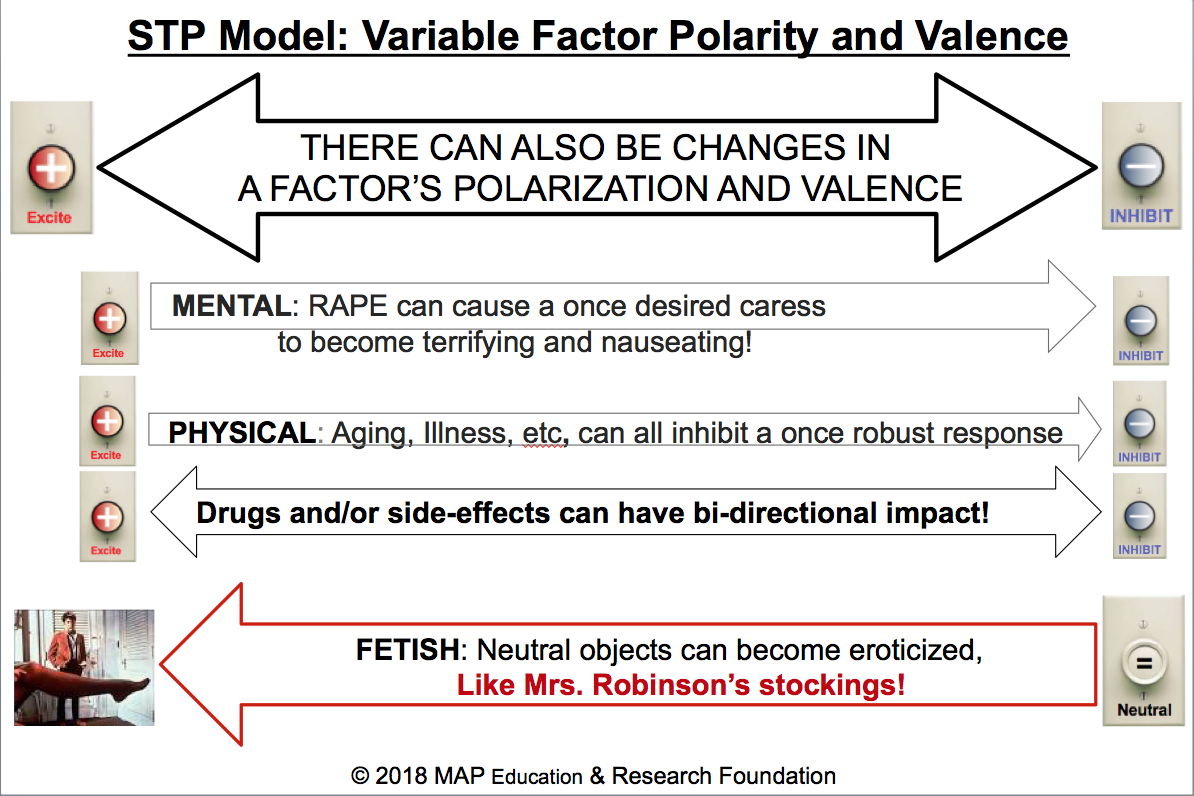

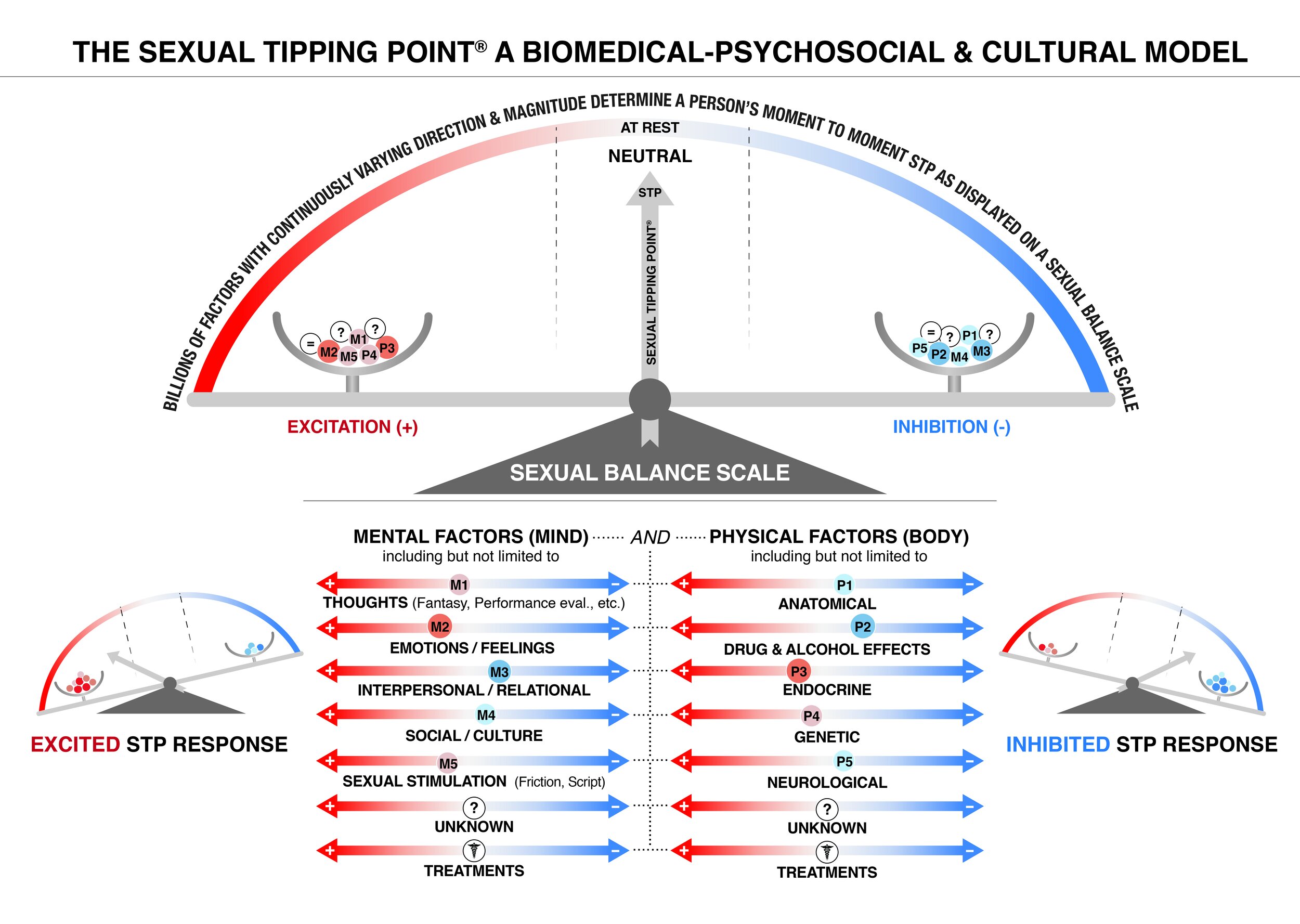

Later the Current Sexual Health publication "The Sexual Tipping Point is a Variable Switch Model" elaborated on the logic and science underlying the recognition that all factors that comprise the STP are continuous and not binary. The article explained how a dimmer switch analogy provides a much more accurate illustration than a plus/minus binary on/off switch. The “variable switch” commentary article also emphasized the rationale for labeling the STP abiomedical-psychosocial and cultural model rather than a biopsychosocial model. It is a fact and obvious that both the mind and body (mental and physical) are always involved in any sexual experience. Accordingly new drawings were created that illustrated both the concepts of variable factor intensity and valence and it is reproduced below. That resulted in a new key to the STP diagram which is shown in the adjacent pane and a download that provides a complete explanation of all the symbols is available on the homepage .

Although, mental health professionals generally successfully raised healthcare provider’s awareness of psychosocial and cultural factors, the majority of physicians who are main providers of healthcare around the world still practice within a medical model (both generally and in treating SD). Realistically, the impact of disease and their treatments needs to be explicitly incorporated into any model used to understand sexual disorders. There is, of course, no question this is also recognized by those who prefer “biopsychosocial,” but we believe that the time is well past due to change the common nomenclature used by sexual healthcare professionals from “biopsychosocial” to “biomedical-psychosocial and cultural.” The latter name describes our best approach to the understanding, diagnosis, and treatment of sexual disorders. As the reasons for the distinction being a meaningful one (that transcends the politic surrounding “medical model versus biopsychosocial”) are already well-detailed elsewhere, they will not be repeated here. However, the interested reader can view the “Sexual Tipping Point” blog for Psychology Today titled “Call It What It Is: Biomedical-Psychosocial and Cultural,” at https://www.psychologytoday.com/us/blog/sexual-tippingpoint/201906/call-it-what-it-is-biomedical-psychosocial-and-cultural. A final reason for embracing “biomedical” is the transdisciplinary vision that emphasizes the integration of sexual counseling with the appropriate use of medical interventions (drugs, devices, surgeries) in order to optimize care for those suffering from sexual disorders (Perelman, 2016). That version characterizes all descriptions of how the STP is to be implemented around the world. That viewpoint is also well illustrated in the Journal of Sexual Medicine article on sex coaching for “Non-Sexological Physicians” (Perelman, 2018). It is high time for physicians and non-physicians alike to incorporate into our nomenclature and promote to the public the phrase “biomedical-psychosocial and cultural” as the term that most accurately describes our current theoretical models for understanding, diagnosing, and treating disorders of sexual response.

The most recent published illustration of the model was developed in conjunction with an expert in graphic information analytics, who suggested that a “slider” moving along its axis would be preferred to a “dimmer” metaphor to communicate the concept of a factor’s dynamic variability. This led to the publication of a Psychology Today STP blog titled “Understanding Sexual Balance: Latest Update to The STP Model,” which introduced the “slider” concept and revised STP images which are now on the Foundation’s website. An additional advantage of the “slider” image is their placement on the multiple axes; thus displaying common factors that affect sexual excitement and inhibition including both medical and psychological treatments and the capability of such a representation to visually display variable polarity and weightings. Here is the cartoon that illustrates that concept.

Two arms on a dynamic balance scale labeled excitation and inhibition hold all the billions of known and unknown exciting (+) and inhibiting (-) factors that variably influence a sex-positive or sex negative response. A person’s STP influencers are selected from the matrix of domain axes listed below the SEXUAL BALANCE SCALE, comprised of potentially relevant mental and physical factors. A factor’s contribution is represented by a “slider” (O) who’s progressively changing hues of red represent varying degrees of excitation, while blue changes in hue indicate the degree of sexual inhibition. Each slider (O) shifts along its axis based on its degree of polarity or (excitation vs inhibition). The size of the slider (O) indicates the weighting (magnitude/ strength) of that factor’s contribution to the person’s sexual response. Diseases and injuries are implicitly noted by a slider’s (O) placement on the axes they impact. The dots separating the mental and physical sides within the matrix reflect how the mind and body are continuously linked; how thoughts/emotions simultaneously transform into biochemical/electrical components and vice versa. Each slider (O) is lettered with an “M” or “P” symbolizing whether it is a Mental or Physical factor, as well as numbered according to the factor it represents. The lettered and numbered sliders (O) are then placed into the arms of the SEXUAL BALANCE SCALE to illustrate the primary factors that determine the STP. Some factors may be neutral (=) while others are not yet discovered (?). The STP is the net sum of all Mental and Physical factors, displayed on a balance scale spanning excitation to inhibition. Each factor's slider setting contributes to the STP’s dynamic representation of any individual’s manifest sexual response at any moment in time.

A personalized STP image can be first used to illustrate to the patient (and partner) the causes of the problem, and then a second image can illustrate which psychological and medical treatments will be used to alleviate/ameliorate the problem.

“Dimmers” Versus “Sliders”

Both the “dimmer” and the “slider” images continue to be used in various presentations and publications about the model, as they both still depict the intra and inter-individual variability of the factors determining the STP. There is significant preclinical research indicating the importance of biological predisposition in sexual disorders. Genetically predetermined thresholds do have a prodigious impact on sexual function (e.g., orgasmic ease and latency time) and tend to distribute similarly to other human characteristics (Perelman, 2016). Yet, the very nature of genetic predisposition and its manifestations are variable. A person may be suffering from a disorder that is primarily biological in its etiology, secondary to genetic predisposition, disease, or pharmaceutical side effects. But despite predisposition, such susceptibility interacts with a variety of psychosocial, environmental, cultural, and medical risk factors resulting in dysfunction or not. The STP model allows for illustrating or imagining a sexual balance beam moving toward greater or lesser excitement/inhibition, as the relevance of various factors are made manifest through sexual history-taking and other diagnostic procedures which will unveil a multilayered conceptualization. For instance, fMRI may suggest that a patient’s diminished desire is the resultof pro-sexual receptor site neurotransmitters being only minimally “turned on” and that others putatively important to avoid inhibiting sexual function do not seem to be shut off (Bloemers et al., 2013; Park & Jeong, 2008). Yet, the reverse can of course contribute to the biological etiology of sexual dysfunction. Or stated from a subjective perspective, for a person to maintain sexual arousal, anti-sexual thoughts (believed to reside in the cortical section) must be inhibited for optimal sexual response (Arnow et al., 2009).

The most recent update to the model in 2022 was to make explicit that both inhibitory and excitatory processes can co-occur, and the balance between these processes determines the overall sexual response. The balance between the opposing forces of excitation and inhibition of all the sliders represents an individual's sexual tipping point. It shows they're transitioning between a sexual and non-sexual state. The dots separating the mental and physical sides within the matrix represent the continuous link between the mind and body. Some factors may be neutral (=) while others remain undiscovered (?). The placement of the sliders on various axes shows the impact of disorders, diseases, and injuries. This most recent illustration, along with a single-page explanation can be found on the home page and is reproduced below:

The STP can serve as a framework that guides the relevant questions. The novice healthcare provider can use the 14 listed factors in the STP matrix (see above figure) to identify and guide their sex status. A sex status is a detailed, focused diagnostic interview that examines all aspects of current sexual functioning in combination with potentially germane historical experiences. For instance, depression is one of the most critical clinical conditions affecting sexual desire, but this relationship is bidirectional. Although medications for depression may affect desire through shared underlying mechanisms, studies have demonstrated that depression itself may have a more significant adverse effect on desire and orgasmic capacity than antidepressant medication side effects (Perelman, 2016b).

A single pathogenetic pathway does not exist for sexual disorders. Assessment requires attention to all medical variables and a thorough sexual history, including an inquiry into masturbatory methods to ascertain the information needed for proper diagnosis and treatment. Just as pathophysiology should not be assumed without medical investigation, psychogenic etiology should not merely be presumed without a sex status examination. The clinician can assess for the degree of immersion and focus on “arousing” thoughts and sensations during sexual activity, including fantasy, watching/reading pornography, and sexy versus anti-erotic intrusive thoughts, e.g., “It’s taking too long!” Fantasy (on the cognition axis) refers to all erotic thoughts and feelings associated with a sexual experience. High-frequency negative thoughts may neutralize or override erotic cognitions (fantasy) and subsequently delay, ameliorate, or completely inhibit sexual response. At the same time, inadequate partner stimulation (friction) may result in an unsatisfying experience (Perelman, 2018). Disappointment over the disparity between the reality of sex with their partner and their preferred sexual fantasy, whether or not unconventional, often identified during discussion of masturbation, is another frequent cause. Finally, communication issues between the partners themselves and/or with their healthcare providers can cause, exacerbate, or interfere with the resolution of sexual difficulties. Before the evaluation concludes, the patient can be offered a formulation that highlights the immediate cause of their problem and how it can be alleviated within the framework of the STP.

Regrettably, we do not yet have a technology so nuanced that it can truly model either our bodies in general or our brains in particular. Further elucidation and understanding of the Sexual Tipping Point® model will occur in time, although it would be very helpful to be able to animate the model in order to make the concepts even easier to visualize using animation or printable “3D model. Unfortunately that is not currently economically feasible. In conclusion. It remains critical to advance a model that will help students, professionals and the public alike understand that sex is always both “Mental And Physical.” Greater success will be found within such integrated thinking. All the biomedical-psychosocial and cultural models of sexual dysfunction provide a compelling argument for sexual medicine treatments that integrate sex counseling and medical and/or surgical treatments (Perelman, 2008b). Given the choice of so many different biopsychosocial models, why embrace the Sexual Tipping Point Model®? Perhaps the greatest advantage of the STP model is its simplicity and the ease with which it provides clinicians as well as their patients (and their partners) with a common sense explanation of sexual problems and potential solutions thus inspiring hope. At Weill Cornell Medicine, when contemplating the clinical need for understanding etiology, diagnosis and treatment, we find the Sexual Tipping Point ® (STP) model particularly helpful and easy to use. The healthcare professional that can accomplish a patient-centered, holistic view of healing within the context of an integrated treatment will offer the most optimized approach and the most elegant solution.

REFERENCES

Abdo, C., Afif-Abdo, J., Otani, F., & Machado, A. (2008). Sexual satisfaction among patients with erectile dysfunction treated with counseling, sildenafil, or both. Journal of Sexual Medicine, 5(7), 1720-1726. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2008.00841.x

Althof, S. E. (2003). Therapeutic weaving: the integration of treatment techniques. In S. B. Levine (Ed.), Handbook of Clinical Sexuality for Mental Health Professionals (pp. 359–376). New York: Brunner-Routledge.

Althof, S., Leiblum, S., Chevret-Measson, M., Hartmann, U., Levine, S., McCabe. M., et al. (2005). Psychological and interpersonal dimensions of sexual function and dysfunction. In T. Lue, R. Basson, R. Rosen, F. Giuliano.S. Khory, & M. Montorsi (Eds.), Sexual dysfunctions in men and women (pp. 73-115). Paris: Editions 21.

Althof, S. E. (2006). Sexual therapy in the age of pharmacotherapy. Annual Review of Sex Research, 17, 116–131.

Althof SE, Perelman MA, Rosen RC (2011), “The Subjective Sexual Arousal Scale for Men (SSASM): Preliminary Development and Psychometric Validation of a Multidimensional Measure of Subjective Male Sexual Arousal.” Journal of Sexual Medicine; 8 (8): 2255-2268.

Althof, SE & Rosen, RC, (2011) Combining medical and psychological interventions for the treatment of erectile dysfunction, In S. B. Levine (Ed.), Handbook of Clinical Sexuality for Mental Health Professionals. New York: Brunner-Routledge.

Althof, S. E., Rubio-Aurioles, E., Perelman, M. A., & Rosen, RC (2012). Standard Operating Procedures for Taking a Sexual History. The Journal of Sexual Medicine, 10(1), 26–35

Balon, R & R. T. Segraves (Eds.), (2005) Handbook of Sexual Dysfunction , Boca Raton: Taylor & Francis.

Bancroft, J. (1999). Central inhibition of sexual response in the male: a theoretical perspective. Neurosci Biobehav Rev, 23(6), 763–784.

Bancroft, J., & Janssen, E. (2000). The dual control model of male sexual response: A theoretical approach to centrally mediated erectile dysfunction. Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews, 24, 571– 579.

Bancroft, J., Herbenick, D., Barnes, T., Hallam-Jones, R., Wylie, K. R., & Janssen, E. (2005). The relevance of the dual control model to male sexual dysfunction: the Kinsey Institute/BASRT collaborative project. Sexual & Relationship Therapy, 20(1), 13–30.

Bancroft, J., Graham, C. A., Janssen, E., & Sanders, S. A. (2009). The Dual Control Model: Current Status and Future Directions. The Journal of Sex Research, 42(2), 121–142.

Banner, L., & Anderson, R. (2007). Integrated sildenafil and cognitive-behavior sex therapy for psychogenic erectile dysfunction: a pilot study. Journal of Sexual Medicine, 4(4 Pt. 2), 1117-1125.

Bloemers, J., Scholte, H. S., van Rooij, K., Goldstein, I., Gerritsen, J., Olivier, B., et al. (2013). Reduced gray matter volume and increased white matter fractional anisotropy in women with hypoactive sexual desire disorder. The Journal of Sexual Medicine. https://doi. org/10.1111/jsm.12410

Feldman HA, Goldstein I, Hatzichristou DG, Krane RJ, McKinlay JB. Impotence and its medical and psychosocial correlates: results of the Massachusetts Male Aging Study. Journal of Urology 1994; 151:54-61

Gladwell, M. The Tipping Point: How Little Things Can Make a Big Difference, Little Brown & Co. New York, 2000

A. Goldstein, C. Pukall, & I. Goldstein, (Eds.). (2009). Female sexual pain disorders: evaluation and management. Oxford, UK: Blackwell Publishing.

I. Goldstein, C. Meston, S. Davis, A. Traish, Women’s Sexual Function and Dysfunction, Taylor & Francis, New York, 2010

Janssen, E., & Bancroft, J. (2007). The Dual Control Model: The role of sexual inhibition and excitation in sexual arousal and behavior. In E. Janssen (Ed.), The Dual Control Model, The Role of Sexual Inhibition and Excitation in Sexual Arousal and Behavior (pp. 197–222). Indiana University Press.

Janssen, E., Vorst, H., Finn, P., & Bancroft, J. (2002). The Sexual Inhibition (SIS) and Sexual Excitation (SES) Scales: I. Measuring sexual inhibition and excitation proneness in men. Journal of Sex Research, 39, 114–126.

Kaplan, H. S. (1974). The New Sex Therapy. New York: Brunner/Mazel.

Kaplan, HS & Perelman, M. A. (1979). The Physician and the Treatment of Sexual Dysfunctions. In G. Usdin & J. M. Lewis (Eds.), Psychiatry in General Medical Practice (pp. 1–27). McGraw-Hill Book Company.

Kaplan, H. S. (1995). The Sexual Desire Disorders: Dysfunctional Regulation of Sexual Motivation. New York: Brunner/ Mazel, Inc.

Kupferman, I. (1991). Hypothalamus and limbic system motivation. In E. R. Kandel, J. H. Schwartz, & T. M. Jessell (Eds.), Principle of Neural Science (3rd ed.). New York: Elsevier.

Leiblum, SR [Ed] Principles and Practice of Sex Therapy. (2007). Principles and Practice of Sex Therapy (4th ed.). Eds: SR & RC Rosen New York: Guilford Press.

Marwick C. JAMA. 1999; 281:2173-2174

Masters, W., & Johnson, V. (1970). Human sexual inadequacy. Boston, MA: Little, Brown.

Masters, W., Johnson, A., & Kolodny, L. (1979). Textbook of sexual medicine. Boston, MA: Little, Brown.

McCarthy, B. W. (1998). Integrating Viagra into cognitive–behavioral couple’s sex therapy. Journal of Sex Education and Therapy, 23, 302.

McCarthy, B. W. (2001). Relapse prevention strategies and techniques with erectile dysfunction. J Sex Marital Ther, 27(1), 1–8.

McCarthy, B. W., & Fucito, L. M. (2005). Integrating medication, realistic expectations, and therapeutic interventions in the treatment of male sexual dysfunction. Journal of Sex and Marital Therapy.

McCarthy, M., & McDonald, D. (2009). Psychobiosocial versus biomedical models of treatment: Semantics or substance. Sex Relat Ther, 24(30), 30–37.

Nelson, C. J. (2006). The impact of male sexual dysfunction on the female partner. Current Sexual Health Reports, 3(1), 37–41. http://doi.org/10.1007/s11930-006-0025-3

Nelson CJ, Mulhall JP. Psychological impact of Peyronie's disease: a review. J Sex Med. 2013 Mar;10(3):653-60.

Parish, SA, Rubio-Aurioles, E. Education in Sexual Medicine: Proceedings from the International Consultation in Sexual Medicine, 2009; The Journal of Sexual Medicine, Volume 7, Issue 10, pages 3305–3314, October 2010

Perelman, M.A. (1984). Rehabilitative sex therapy for organic impotence. In T. Segraves & E. Haeberle (Eds.), Emerging dimensions of sexology (pp. 181–188). New York, NY: Praeger.

Perelman, M. A. (2003). Sex coaching for physicians: combination treatment for patient and partner. International Journal of Impotence Research, 15 Suppl 5, S67–74.

Perelman, M. A. (2005) Combination therapy for sexual dysfunction: integrating sex therapy and pharmacotherapy. In R. Balon & R. T. Segraves (Eds.), Handbook of Sexual Dysfunction (pp. 13–41). Boca Raton: Taylor & Francis.

Perelman, M. A. (2005) Psychosocial evaluation and combination treatment of men with erectile dysfunction [Review]. Urologic Clinics of North America, 32, 431–445.

Perelman, M. A. (2005). Idiosyncratic Masturbation Patterns: A Key Unexplored Variable in the Treatment of Retarded Ejaculation by the Practicing Urologist. Journal of Urology, 173(4), 340.

Perelman, M. A. (2006a). The Sexual Tipping Point: A model to conceptualize etiology, diagnosis & combination treatment of female & male sexual dysfunction. Journal of Sexual Medicine, 3(Suppl. 1), 52.

Perelman, M. A. (2006b). A new combination treatment for premature ejaculation: a sex therapist's perspective. Journal of Sexual Medicine, 3(6), 1004–1012.

Perelman, M. A. (2008). Integrated sex therapy: A psychosocial-cultural perspective integrating behavioral, cognitive, and medical approaches. In C. C. Carson, R. S. Kirby, I. Goldstein, & M. G. Wyllie(Eds.), Textbook of erectile dysfunction (2nd ed., , London, England: Informa Healthcare. pp. 298–305)

Perelman, M. A. (2009). The sexual tipping point: a mind/body model for sexual medicine. Journal of Sexual Medicine, 6(3), 227–632.

Perelman, M. A. (2014a). The history of sexual medicine. In APA Handbook of Sexuality and Psychology, Vol. 2: Contextual Approaches (pp. 137–179). Washington: American Psychological Association.

Perelman MA (2014b)."Delayed Ejaculation," in Principles and Practice of Sexual Therapy 5th edition, [Eds:YM Binik and KS Hall], Guilford Press, New York.

Perelman, M. A. (2015). Advocating For a Transdisciplinary Perspective in Sexual Medicine. Current Sexual Health Reports, 7(1), 1–2.

Perelman, MA, & Watter D (2016a) “Delayed Ejaculation,” in Handbook of Clinical Sexuality for Mental Health Professional [Eds: Levine S, Risen C, Althof S, Brunner Routledge, New York, NY.

Perelman MA, (2016b) “Introduction: Advocating For Transdisciplinary Treatment Of Sexual Dysfunction Employing A Biopsychosocial-Behavioral & Cultural Approach. In Management Of Sexual Dysfunction In Men And Women: An Integrated Approach” [Eds: Lipshultz L, Pastuaszak A, Giraldi A, Goldstein A, Perelman MA, Springer, New York, 2016.

Perelman MA, (2016c) “Epilogue: Cautiously Optimistic For The Future of A Transdisciplinary Sexual Medicine In Management Of Sexual Dysfunction In Men And Women: An Integrated Approach” [Eds: Lipshultz L, Pastuaszak A, Giraldi A, Goldstein A, Perelman MA, Springer, New York, 2016.

Perelman, MA, Why The Sexual Tipping Point is a Variable Switch Model. Current Sexual Health Reports, 10: 38. Springer Publications, 2018.

Perelman, MA. (2021) “The Sexual Tipping Point®: A Biomedical-Psychosocial & Cultural Model,” In P. Nobre et al (eds), Encyclopedia of Sexuality and Gender, Springer International Publishing AG.

Pfaus J. Pathways of sexual desire. Journal of Sexual Medicine. 2009; 6(6):1506-1533.

Phelps, J. S., Jain, A., & Monga, M. (2004). The PsychoedPlusMed approach to erectile dysfunction treatment: The impact of combining a psychoeducational intervention with sildenafil. Journal of Sex and Marital Therapy,30, 305-314.

Rosen, R. C., Leiblum, S. R., & Spector, I. P. (1994). Psychologically based treat ment for male erectile disorder: A cognitive-interpersonal model. Journal of Sex and Marital Therapy, 20( 2), 67-85. This delineates the authors' cognitive-interpersonal-behavioral model for treating ED.

Rosen, R. (2000). Medical and psychological interventions for erectile dysfunction: Toward a combined treatment approach. In S. Leiblum & R. Rosen (Eds.), Principles and practice of sex therapy (3rd ed., pp. 276–304). New York, NY: Guilford Press.

Rosen RC, Miner, MM, Wincze JP. (2014) Erectile dysfunction: integration of medical and psychological approaches. In: Binik YM & Hall KSK, editors. Principles and practice of sex therapy, 5th edition. New York. Guilford Press..

Rosen, R., Janssen, E., Wiegel, M., & Bancroft, J. (2006). Psychological and interpersonal correlates in men with erectile dysfunction and their partners: a pilot study of treatment outcome with sildenafil. Journal of Sex & Marital Therapy,

Rowland, D. L., Patrick, D. L., Rothman, M., & Gagnon, D. D. (2007). The psychological burden of premature ejaculation. The Journal of Sexual Medicine.

Symonds, T., Roblin, D., Hart, K., & Althof, S. (2011). How Does Premature Ejaculation Impact a Man’s Life? Journal of Sex &Marital Therapy, 29(5), 361–370.

Tiefer, L. (1994). Three crises facing sexology. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 23, 361-374. doi: 10.1007/BF01541403.

Tiefer, L. (2001). The “consensus” conference on female sexual dysfunction: Conflicts of interest and hidden agendas. Journal of Sex and Marital Therapy, 27, 227-236. doi: 10.1080/00926230152052049.

Titta, M., Tavolini, I., Moro, F., Cisternino, A., & Bassi, P. (2006). Sexual counseling improved erectile rehabilitation after non-nerve-sparing radical retropubic prostatectomy or cystectomy—Results of a randomized prospective study. Journal of Sexual Medicine, 3, 267-273. doi: 10.111/j.1743-6109.2006.00219.x